- Home

- Chris Van Allsburg

The Chronicles of Harris Burdick: 14 Amazing Authors Tell the Tales Page 2

The Chronicles of Harris Burdick: 14 Amazing Authors Tell the Tales Read online

Page 2

***

I went back to sweeping every Wednesday.

Grandma went back to saying:

All that glitters is not gold.

Beware the calm before the storm.

Those pants make you look fat.

***

A week passed. Nothing happened. I might have dropped a few eggshells, a bag of stale cookies, and a turkey neck or two in a certain corner of the living room to keep things calm. There were no more outbursts, no more attacks.

Everything was fine.

***

Two weeks passed and it happened again.

That morning, Grandma said:

Silence is golden.

An empty barrel makes the most noise.

Where did that cat disappear to?

I followed a trail of cat hairs out of the kitchen.

I knew where this trail was leading, but I followed it anyway. I followed the trail into the living room. I followed the trail to the edge of the rug.

I slowly ... carefully ... lifted up one corner of the rug with the end of my broom. Nothing. A smudge of dirt, a single small tuft of red cat fur, a dusty copper penny.

Then it attacked.

A mad tangle of dust, dirt, fur, yellow hardened cake crumbs, moldy bones, eggshells, turkey necks, liver-flavored Kibbles 'n Bits, fingernail clippings, cat pieces, hair, fangs, and those two red eyes lunged for my leg.

The Dust Devil had turned into a Dust Demon!

I stopped the hungry monster's charge with the bristles of my broom. I flattened the awful thing with the smack of a chair. It heaved. It snarled. I swept it back under the rug.

I should have listened to Grandma. It could have saved a life.

But the Dust Demon needed more. And there was only one thing to do.

I remembered something else Grandma said:

Don't put off until tomorrow what you can do today.

I figured it was the least I could do, listen to her one last time.

I called, "Grandma? Could you come into the living room?"

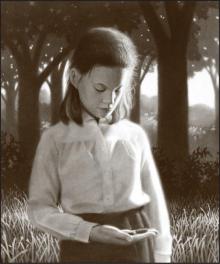

A Strange Day in July

He threw with all his might, but the

third stone came skipping back.

A STRANGE DAY IN JULY

SHERMAN ALEXIE

Because it was summer and it was hot and Timmy and Tina were ten years old, they sat on the park bench and slurped chocolate ice cream cones.

"When you get to the middle of your ice cream," Timmy said to Tina, "you're going to find a big white spider."

"When you get to the middle of your ice cream," Tina said to Timmy, "you're going to find a swarm of bees."

"Ha," Timmy said. "A swarm of bees couldn't fit inside an ice cream cone."

"They're the smallest bees in the world," Tina said. "And there's three million of them inside your ice cream."

"Well," Timmy said, "after you eat the spider in your ice cream, it's going to build a web in your stomach and catch all the food you eat, and you're going to starve to death."

"That's so gross," Tina said, and she just kept eating her ice cream. Timmy kept eating, too. They were brother and sister and they loved chocolate ice cream more than they loved each other. Heck, if they had discovered severed thumbs in the middle of their ice cream, Timmy and Tina would have just licked them clean and dropped them into a fish tank.

Okay, that's not true.

If Timmy and Tina had discovered severed thumbs in their ice cream, they would have screamed, thrown cones into the air, and run crying for home.

Or maybe not.

Timmy and Tina were very strange children. And maybe, just maybe, they might have been the kind of kids who enjoy finding severed thumbs in their ice cream. Yes, Timmy and Tina were exactly that strange. Everybody said so. Even their mother and father said so.

"My children," their father often said. "You are mine, and I love you, and you are so very cute and pretty, but you are aliens from a planet called Weirdatron."

When Timmy and Tina walked in the woods, the birds would shake their tail feathers and flutter their wings and sing, strange kids, strange kids, strange kids.

Okay, that's not true, either.

But Timmy and Tina scared birds. And they scared dogs. Heck, the lions at the zoo would cover their faces with their paws whenever Timmy and Tina came to visit.

Okay, that's not true at all.

But Timmy and Tina were the strangest kids in town. They might have been the strangest kids in the state. In the country. Maybe in the whole world. And they were strange in exactly the same way. And with chocolate smeared all over their faces, and all over his blue shirt and her blue dress, they looked exactly alike, too. Well, except for the fact that one of them was a boy and the other was a girl.

"Oh, look at you two," an old woman said to Timmy and Tina as she stopped near them. "I don't think I've ever seen a cuter set of twins in my whole life."

"We're not twins," Timmy said.

"We're triplets," Tina said.

"There's three of you," the old woman said. "How wonderful! Where's the other one?"

"She died," Timmy said.

"Oh, I'm so sorry," the old woman said. "Your little hearts must be broken."

"She was killed in a car wreck," Tina said.

"When we were five years old," Timmy said.

With tears in her eyes, the old woman pulled the kids close and hugged them. She wanted to squeeze the sadness out of their bodies. But she only managed to squeeze the ice cream cones out of their hands. And there's nothing more irritating than an ice cream cone dropped in the dirt. Well, except for two ice cream cones dropped in the dirt.

Timmy and Tina were very angry about the wasted ice cream. They were angrier than they'd ever been. You might think that Timmy and Tina would have been angrier when their sister died. But here's the thing: Timmy and Tina didn't have a sister, alive or dead. Timmy and Tina weren't triplets. They were only twins, which is still pretty cool, but not nearly as cool as being triplets.

"But why are you here in the park by yourself ?" the old woman asked. "Where are your parents?"

"They died in the car wreck, too," Tina said.

"We're orphans," Timmy said.

They were lying, of course. Their mother and father, exhausted by their children's strangeness, were napping on a picnic blanket only twenty feet away.

"But who takes care of you?" the old woman asked.

Timmy and Tina looked at each other. They read each other's minds. They knew exactly what lie they wanted to tell. And they wanted to tell it together.

"We were adopted by an old woman," they said. "And we lived in a trailer house with one hundred cats. And the old woman fed the cats but she didn't feed us. And she whipped us, too. And sometimes she would pick up a cat, shake it until it was spitting mad, and then throw it on us."

"Oh, my Lord," the old woman said. "That's the most horrible thing I've ever heard."

"That's not even the worst part," Timmy and Tina said. "You know what's really horrible?"

"What? What?" the old woman asked.

"That old woman looked exactly like you!" Tina and Timmy screamed. They chanted: "She looked like you! Exactly like you! She looked like you! Exactly like you! She looked like you! Exactly like you!"

As they chanted, the old woman let them go and stumbled backwards.

"Exactly like you! Exactly like you! Exactly like you!"

The old woman turned and ran. Well, she was old, and so she really just walked as fast as she could. And her fast was slow, so Timmy and Tina were able to follow her easily.

"Exactly like you! Exactly like you! Exactly like you!"

So, yes, Timmy and Tina were strange. And they were cruel. They were strangely cruel. And they might have chased the old woman for a hundred miles. But it so happens that strangely cruel children get bored quickly. So Timmy and Tina let the old woman go. And they laughed.

"That was fun," Timmy said.

"It was sad, too," Tina said.

"Why was it sad?" h

e asked.

"Because I really wish we were triplets," she said.

"Yeah, that would be cool."

"You know what?"

"What?" he asked.

"We should pretend we're triplets," Tina said.

"Okay," Timmy said. "But how long should we do that?"

"We should pretend it," she said, "until everybody thinks we're crazy."

"No," he said, "we should pretend until everybody else goes crazy."

And so, later that night, after they got home, Timmy and Tina pulled an old dress out of her closet and took it with them to dinner. Timmy held on to the left sleeve and Tina held on to the right sleeve, and they skipped down the stairs with their imaginary sister, over to the dinner table, and gently draped her over a chair.

"Who is that supposed to be?" their father asked.

"That's our sister," Tina said.

"We're triplets," Timmy said.

Their father looked at the dress, at the imaginary sister, then at his wife. She shrugged her shoulders, as if to say, This is just one more strange night in a lifetime of strange nights.

"Well," their father said, "your sister looks rather skinny. She should eat something."

And so their mother filled five plates with chicken and potatoes and green peas, and four people ate well, but the fifth wouldn't eat a thing. She just stared at her food.

"Why isn't your sister eating?" their mother asked.

"Because she's mad," Tina said.

"Why is she mad?" their father asked.

"Because she doesn't want to go to school tomorrow," Timmy said.

Because they were weird kids and because weird kids were often punished, Timmy and Tina had to spend their summer going to school.

"Oh," their mother said. "I know that at least two of you have to go to school in the morning."

"If she doesn't go to school," Tina said, and pointed at the dress draped over the chair, "then I don't have to go to school."

"If you make us go to school and let her stay home," Timmy said as he also pointed at the dress, "then I will scream at the teacher until she cries."

Timmy was telling the truth. Three times in the last school year, he had screamed at his teacher until she cried. So what would be worse? A teacher weeping in the adult bathroom or two strange kids carrying around an empty dress at school?

"Okay," their father said. "Your sister has to go to school tomorrow."

"Don't tell us," Tina said.

"Tell her," Timmy said.

Their father sighed. He put his head in his hands. He wondered why he hadn't become an astronaut. He could be orbiting the earth, thousands of miles away from his strange life. But he loved his children. He did. And he loved his wife. He did. And he wanted to make all of them happy, so he did his best.

"Okay, young lady," he said, and pointed at the dress, "you are going to school tomorrow."

"Daddy," Tina said, "she's not going to listen unless you say her full name"

"Yeah," Timmy said. "Parents always use kids' full names when they're mad."

"Okay," their father said. "What's her name?"

Timmy and Tina laughed.

"She's your daughter," Tina said.

"We didn't name her," Timmy said. "You did."

"You and Mommy," Tina said.

Their parents looked at each other. What should they do? They read each other's minds.

"Okay, Mary Elizabeth St. Pierre," their father said to the empty dress. "You are going to school tomorrow. And I don't want to hear another word about it."

So, early the next morning, Timmy brushed his imaginary sister's imaginary teeth, and Tina combed her imaginary sister's imaginary hair, and they poured her a bowl of cereal she wouldn't eat and a glass of orange juice she wouldn't drink, and all three of them put on their shoes and raced to catch the bus.

On any other school bus in the world, it would have been strange to see a brother and sister carry an empty dress down the aisle. But this was Timmy and Tina's regular bus. They'd been riding this bus since kindergarten. So nobody was surprised by the strange behavior. In fact, most of the kids didn't even notice it.

But Timmy and Tina, being who they were, would not be ignored.

"Everybody, listen!" Timmy shouted. "This is our sister, Mary Elizabeth."

"Mary Elizabeth St. Pierre," Tina added.

The kids all stared at the empty dress. Then they went back to their books and video games and cell phones.

"Okay," Timmy said. "If you don't all say hello to our sister, I am going to stand outside your bedroom windows and stare at you as you sleep."

Timmy had never done such a thing, but all of the kids figured he was fully capable of it, so they took him seriously.

"Hello!" all of the kids said to the empty dress.

"Say her name!" Tina shouted.

"Hello, Mary! " the kids shouted.

"Her full name!" Timmy shouted.

"Hello, Mary Elizabeth! " the kids shouted.

"Her fullest full name!" Tina and Timmy shouted together.

"Hello, Mary Elizabeth St. Pierre!" the kids shouted.

Timmy and Tina were very pleased. Mary Elizabeth St. Pierre was also pleased. She spun left and right and bowed. She was obviously a very proper and polite empty dress.

Soon enough, the bus pulled up next to the school, and Timmy and Tina and Mary Elizabeth hurried to their classroom. It's a well-known fact that empty dresses hate to be late for class. So Timmy and Tina rushed to their desks. They sat across the aisle from each other and held the dress like a flag between them. A blue flag covered with yellow flowers.

"Timmy and Tina," their teacher said, "what are you two up to now?"

"Three," Timmy said.

"Three?" their teacher asked.

"Three," Tina said.

"Three what?" their teacher asked.

"There's not two of us," Timmy said.

"There's three of us," Tina said.

"We're triplets," they said together.

Because of Timmy and Tina, their teacher had often cried in the classroom. She'd also cried during her drive to school. And she'd cried when she woke and realized that she had to drive to school. And she'd cried before she'd fallen asleep at night when she realized she'd have to wake and go to school again.

That's a lot of crying. That's a lot of tears. Ten million tears, to be exact. The teacher had counted them.

Their teacher's lips trembled. Her hands shook. Her heart was a radio blasting rock-and-roll at maximum volume. But she wasn't going to cry this time! No way! She would not let these strange kids make her weep in public ever again!

So she calmly walked up to the chalkboard and wrote the three hardest math problems she could think of. They were geometry questions, about squares and triangles and circles and three dimensions and a number that started out as 3.14 but kept going and going and going like an endless snake. These kids were only ten years old. She'd never taught them a thing about geometry. Not really. And certainly not about any math this complicated.

"Okay," the teacher said. "I would like three volunteers to come up and solve these problems."

All of the kids, even Tina and Timmy, froze. They knew they couldn't solve those problems. They couldn't figure out why their teacher expected them to know the answers.

"Timmy and Tina," their teacher said. "Would you, and your sister, please come up and work the board?"

Timmy and Tina groaned. They didn't want to do it. They were mad. But their sister was even angrier. Empty dresses hate geometry. Timmy and Tina looked at each other. They read each other's minds. They knew what to do. So they walked up to the chalkboard. Tina held a piece of chalk in her left hand and another piece in her right hand, which also held the empty dress's left sleeve. Timmy held a piece of chalk in his right hand and another piece in his left hand, which also held the empty dress's right sleeve.

Two kids and an empty dress! Triplets! With four pieces of chalk! And all four of them wrote the same

thing in big block letters:

THIS IS NOT FAIR!

And it wasn't fair! Not at all! Timmy and Tina and Mary Elizabeth St. Pierre weren't bad kids, were they? No, they were rebels! They were fighting against an evil teacher!

"This is not fair!" Tina shouted.

"This is not fair!" Timmy shouted.

They shook the empty dress as if she were dancing. As if she were leading a parade.

"This is not fair! This is not fair! This is not fair!" Tina and Timmy chanted. And soon enough, the other kids joined with them. They all stood at their desks, pumped their fists in the air, and joined the protest.

"This is not fair! This is not fair! This is not fair!"

With the empty dress leading them, Timmy and Tina and the other kids marched out of the classroom. But because they were only ten years old, most of the kids stopped marching at the school doors, but Timmy and Tina kept marching. And chanting. And marching. And chanting.

They marched and chanted their way along the highway and out of town, down the dirt path, past a red barn, and to the shore of Lake Green. With Mary Elizabeth St. Pierre swinging between them, Timmy and Tina danced in the sand. It was a strange dance, of course. They jumped high in the air. They clapped their hands and clicked their heels. They made sand angels. They spun in circles and spat like sprinklers. They howled like wolves at the bright sun and the moon barely visible on the horizon.

"We are magic!" Timmy shouted.

"We are magicians!" Tina shouted.

"We can make anything come true!" they shouted together.

And then a strong and clever wind ripped Mary Elizabeth St. Pierre out of their hands and sent her drifting ten, twenty, thirty feet over and into the water, where she floated like a dress-shaped boat.

Timmy and Tina silently stared at the blue and yellow dress floating on the black water. It floated away from them.

"Don't you hate it when she does that?" Tina asked.

"Yeah, she thinks she's so much better than us," Timmy said.

The Chronicles of Harris Burdick: 14 Amazing Authors Tell the Tales

The Chronicles of Harris Burdick: 14 Amazing Authors Tell the Tales The Chronicles of Harris Burdick

The Chronicles of Harris Burdick